#57 Improving Saturators

I recently spent time fixing the gain normalization in Valentine’s waveshapers. After a brief detour to a UI topic (more on this later), I decided to take a look at how the waveshapers use Antiderivative Anti Aliasing. I won’t go deep into the theory here, as it has been covered more comprehensively and clearly by people smarter than me. Comparing the examples linked here to what I had implemented, I noticed something odd.

Generally, first order ADAA is calculated as follows: y = (F(x) - F(x1)) / (x - x1), where F(x) is the antiderivative of the function to which antialiasing is being applied (f(x)). This calculation can cause a divide by zero when the difference between the current and previous sample is small enough. In this case we use function’s standard version: y = f(x).

if(x - x1 < tolerance)

{

y = f(x);

}

else

{

y = (F(x) - F(x1)) / (x - x1);

}

What is “small enough”? For float, that’s around 1e-7 (estimating based on std::numeric_limits<float>::epsilon()). I noticed that my implementation was using a higher tolerance: 1e-3. This was, if I recall correctly, a value suggested by a mentor. Looking at it again, and seeing an example that used a much lower tolerance, I thought (see note below about this) “surely it should be lower—after all, we want to use the interpolated calculation as much as possible”. Lowering the tolerance, however, degraded the sound of my inverse hyperbolic sine waveshaper: small signals now had a halo of what sounded like quantization noise, and large signals had extra high end hash. Kind of the opposite of what I wanted.

Did I get something wrong? I verified that I was correctly calculating the antiderivative. The only thing I could think of us how I was calculating the inverse hyperbolic sine. When I first implemented this function, I didn’t know that the C++ standard library had one of its own. So I looked up the calculation and used that:

inline float Saturation::inverseHyperbolicSine (float x)

{

return log (x + sqrt (x * x + 1.0f));

}

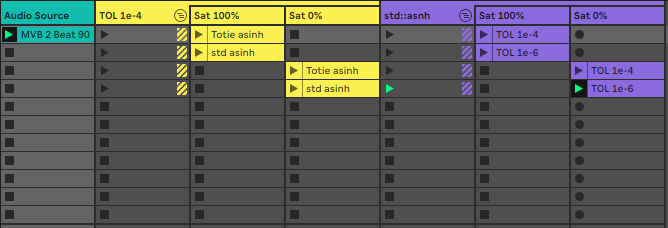

Maybe using the STL version would work better. But how would I know? The issue was easy to hear—so I quickly put together a Live session that would allow me to evaluate my changes.

Generally, I found that std::asinh sounded better than what I had implemented. This was evident in both small and large signals. Using the STL implementation allowed me to use a slightly lower tolerance than I was using before (1e-4). Lower tolerances caused noisy output, especially noticeable for small signals.

I also found that a smaller tolerance could be used for tanh without the noise I was getting for asinh.

A note about reasonable but wrong assumptions: I messaged Jatin Chowdhury, who I linked above, regarding my assumption that we want to use the interpolated calculation as much as possible. It turns out that my thinking was turned around. The fact that we use the conventional calculation when we would otherwise have a divide by zero doesn’t mean that we have an edge case. We can’t reason, then, that we want to use the interpolated calculation as much as possible.

This makes sense if we consider what the difference between two sequential samples approacing 0 really means. The amount of change between samples is directly related to frequency. So, to grossly generalize, lower frequencies will trigger the conventional branch and high frequencies will trigger the interpolated branch. We’re ok with this because we’re not worried about low frequencies causing aliasing.